|

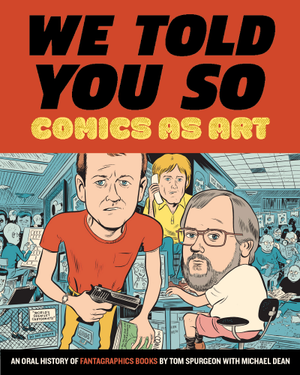

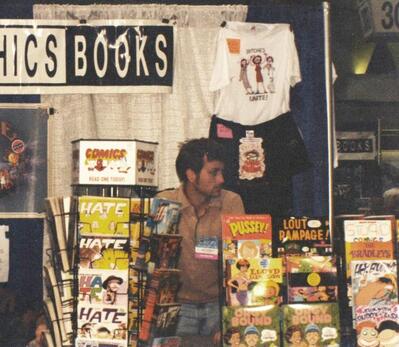

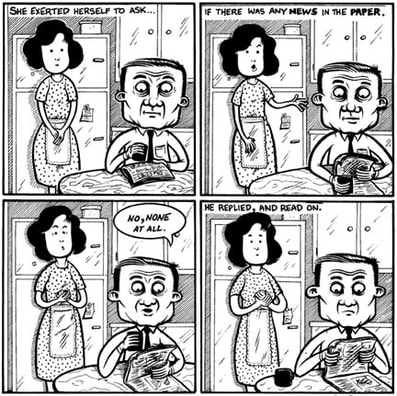

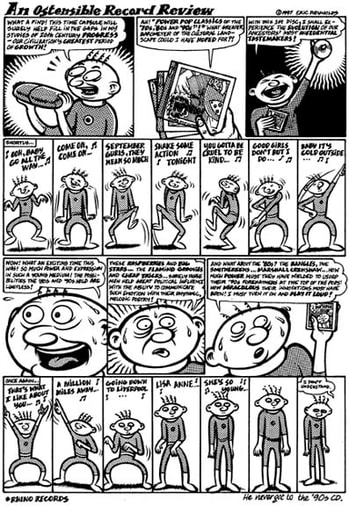

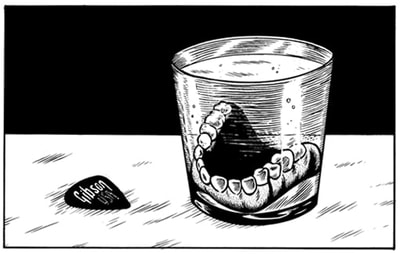

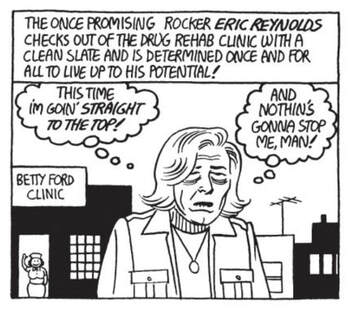

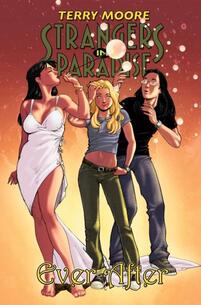

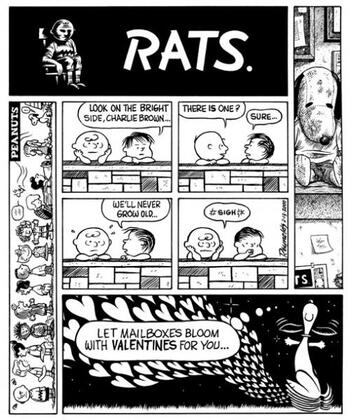

Lion's Tooth co-founder Cris Siqueira in conversation with Fantagraphics publisher and cartoonist Eric Reynolds Cris Siqueira first visited Fantagraphics Books in 1997 to interview the company’s late co-owner Kim Thompson. She went back twenty years later for a conversation with cartoonist and publisher Eric Reynolds Eric Reynolds is one of the most well respected and loved figures in the world of alternative comics. He is loved by cartoonists, loved by fans, loved by booksellers, and loved by journalists like myself. When he was director of marketing and public relations at Fantagraphics Books, Eric facilitated many of the interviews with cartoonists that I conducted during a trip to the US in 1997. Here’s a complete list of the people I met back then, and the people I have been interviewing again for this series. In my first visit to the Fantagraphics headquarters in Seattle 20-some years ago, I talked to legendary publisher and co-owner Kim Thompson, who sadly passed away in 2013. I came back in 2017, and this time sat down for a conversation with Eric Reynolds, who is now co-publisher at Fantagraphics. A cartoonist himself, Eric was The Comics Journal news editor and played guitar and sang in the band The Action Suits (with Al Columbia, Peter Bagge, and others). Although this conversation is almost three years old, it is a great reflection on comics today and how the industry has evolved—all from an extremely knowledgeable and insightful insider. This interview has been edited for clarity. Cris Siqueira, Feb 6 2020 - Intro and excerpt featured in the Milwaukee Record How did you first get involved with comics? Eric Reynolds: I was a lifelong comics fan. I never thought I’d work in comics because it didn’t even seem like a legitimate career. I never even thought about it, but I always drew. Long story short, when I got into college, I was studying journalism, but through a strange twist of fate, I ended up interning in Fantagraphics and never leaving, basically. How old were you when you started? Eric: Here? I had just turned 22. It was my 22nd birthday, literally a couple of days before I started here. Did you publish your own comic books? Eric: Yes. I did comics all growing up. I drew comics, I copied comics. When I was in college, I was the managing editor of the university paper. Like I said, I was studying journalism, but I was also the staff cartoonist, and did comics strips and editorial cartoons. Where did you go to college? Eric: University of California at Irvine. I even won a couple of awards from the journalism student organization. I was always doing comics, and continued after I started working here, doing many comics and collaborating with other cartoonists that I was friends with. I don't do comics as much anymore, but I still draw a lot, and try to keep my chops up. Do you do anything with your drawings? Eric: Not really. I’ve gotten to the point in my life where I stopped drawing comics. I’ve been so invested in Fantagraphics that I lost interest in doing my own comics. I still draw a lot. In fact, I draw more now than I have over the past 20 years. The thing I like the most about it is that I don’t do anything with it. It’s just for me and my sketchbook at night. It’s actually been really freeing to not worry about that stuff, because that’s what I do all day long with other Fantagraphics authors. I’m much better off not worrying about that stuff for myself and just doing it for the sake of it. Not everything has to become a product. Eric: Right. I think when I was in my 20s I didn’t realize that. Everything was like trying to accomplish something, trying to do something. I was always trying to do illustration work, chasing illustration work, chasing other little gigs here and there. Maybe that speaks to how little money there is, how hard it is to make a living in comics…but at a certain point, I realized I didn’t want to do that. I really realized it for myself, I felt like I was doing more good at Fantagraphics than trying to do my own thing. When we first met in 1997, the boom of the ’80s had already passed, but the cartoonists I interviewed seemed very ambitious, and there was a feeling that they could “make it” any minute. How do you feel about what has happened to the industry since then? Eric: I have so many mixed feelings about it. All that stuff about, “Oh, we’re going to make it big.” In a lot of ways it did happen, but in a lot of ways it didn’t. Even someone like Dan [Clowes], who has probably become one of the most successful cartoonists of that generation, he doesn’t have mass, mainstream success. It’s just success. You’re still talking about relatively smaller numbers. What comics have mainstream success now? Eric: Something like The Walking Dead or Raina Telgemeier and some of the books for younger readers, like Bone. Dan Clowes is still- I mean, he's a literary success. Whether I'm talking about prose or comics, it's a relative success. The part that's really encouraging about it is that their comics have become a respected art form in literary circles, in a way that definitely was what we aspired to… to be a literary success type of author who gets published in The New Yorker or something like that. It's not Stephen King. It's not John Clancy. And that's fine. Even back in the 90s Dan Clowes was the most successful cartoonist I interviewed. Before I met him I talked to some people who were really struggling and even thinking about quitting comics. But when I got to Clowes he said he was glad not to be mainstream or overly successful. Eric: I think that's what Dan (Clowes) would still tell you, that it’s a good thing. What he told you 20 years ago, I think he would still say it is true, even though he had some relative success compared to some of his peers. At that period in the '90s, you're right, that was a real crucial point in the development of that generation of cartoonists, and also just the development of the art form because those guys were really cutting edge at the time. That generation of comics makers were reinventing the wheel more than any generation had, at least since the underground cartoonists of the late 60s, and I think they paved the way more than really anybody has since then. The underground guys paved the way to just doing whatever you want, but they were still very transgressive. I feel that 80s generation took that freedom and ran with it in a more mature, sophisticated storytelling way. They took it beyond the art, or the visuals. Eric: They were better fiction writers. They were better comics makers, too, just in terms of telling a sustained narrative. They really paved the way for everything that's happening now. I think that extends to people like Raina Telgemeier and the successful YA [young adults] books that you have now. I don't think you could have that today without stuff like Love and Rockets paving the way. And also the fact that you don't have to explain yourself anymore, you don't have to say, "No, I don't do Spider-Man. I don't do Garfield. I do the stuff for grownups who just enjoy literature and enjoy visual literature." By the same token, pop culture has become so dominant that it's also two steps forward, one step back, or even one step forward, two steps back. Like the Comic-Con in San Diego is such a mainstream phenomenon. I only went that one time when we met. I remember Fantagraphics and Drawn & Quarterly were across the aisle from Danzig [Verotik]. I can't imagine what the convention is like now. Eric: I remember those days. It hasn't changed that much, to be honest. There's just fewer people like Fantagraphics. There used to be Fantagraphics, Drawn & Quarterly, Last Gasp, Giant Robot, Sparkplug, Black Eye. Now, it's literally just Fantagraphics, Drawn & Quarterly and Giant Robot. We're just surrounded by Danzigs now. [laughs] How can you afford getting hotel rooms? Back then you suggested an affordable hotel. Last time I looked it up it was nuts. Eric: They're crazy expensive. We bring fewer staff now than we used to back then. Did you go in '97? Yes. Eric: At that point we probably still had ten 10x10 booths. It was two rows, back-to-back. Now, we have two 10x10 booths. The space we have keeps shrinking. And every year, it's like, “So and so's not coming back”. I think we manage it because we've been going for so long, we're a little more established in the comic book world than a lot of alternative publishers. And we're on the West Coast already. So alternative comics got recognition but actually lost space in the mainstream? Okay, for a specific example, in 2000, you had Jimmy Corrigan, and David Boring, and one of Ben Katchor's Julius Knipl books [Julius Knipl, Real Estate Photographer: The Beauty Supply District]. You had this critical mass of stuff coming out around 2000 that felt like the culmination of everything the '80s was building towards. You had mainstream successes amongst these fringe artists, guys like Clowes, Charles Burns, Ben Katchor, Chris Ware. Did Ben Katchor get the super recognition the other guys did? Eric: Katchor is still a fringe guy, but his work was coming out from Pantheon, a big publisher. You had all these big books coming out, and it really felt like, "This is it, we've done it. We've accomplished what we set out to do." Then in 2001, you had the first Sam Raimi Spider-Man movie come out. Just like that, overnight, the culture was embracing superheroes. Before it felt like superheroes were rightfully becoming marginalized so this other stuff could become successful. Then it just reverted right back to the way it was. And we’re stuck with all those unwatchable movies. Eric: A movie like Ghost World, that came out in 2001, I don't think Ghost World would get made today. It has a Brazilian cinematographer. Eric: That's right. Affonso Beato. For the longest time it was hard for me to be excited about new comics. Now there’s finally a new generation of cartoonists I like. Simon Hanselmann is probably my favorite. Eric: Yes, Simon is great, I love his work, too. He’s a good writer. I think there’s plenty of really good work being done, and I think Simon’s definitely a great example. Today, I feel like everything positive comes with a caveat. I think there is really great work being done, but I do understand what you’re saying when you said you hadn’t been excited about comics for a long time. I can relate to that. I think the reality is probably somewhere in between, where your lack of enthusiasm is probably justified on some level, but I also think that if you were digging a little deeper, you could have found the good stuff. I certainly experienced that. I go through phases where I’m not super excited by some of what I see in contemporary comics, but sometimes I think that’s me being a little lazy too, and if I look hard enough I can find plenty of really good work. Is it part of your job to find and publish new people? Do you get submissions? Eric: It’s less so the submissions than just staying engaged with the comics community. I feel like we have a prerogative to be proactive and look for good stuff. I say that because I know how easy it can be to just sit back. I’m working on books nonstop, so I always have a stack of proofreading and a stack of stuff to read. I always have more shit to read with Fantagraphics than I can handle at any one time. So it doesn’t always leave a lot of time to go out and actively search for new comics, but I have to do it. I go through phases where I struggle with it and I tell myself like, “Okay, I’ve got to engage.” I guess that’s the best way to put it. There’s so much stuff on social media too, I can’t imagine how you curate it. There’s terrible art mixed together with great art, and a lot of noise in the middle. Eric: Now you just have a lot more people who identify as cartoonists, and so you have a lot more good work and a lot more shitty work. Democracy is never bad, right? It's good to have all this shitty work [laughs]. Eric: It's just part of the engine that keeps it all chugging along. I feel like I end up going back to the same sources and probably missing out on a lot of good things. Eric: If you know what you want, it’s so much easier to find it, and that’s great. I think I could put on my old man hat and complain about how it’s not as good as it was back then or whatever, but I think the thing that is different about what you just described and that I miss the most is the gatekeepers, the tastemakers that you could trust to steer you in the right direction, even if you didn’t know exactly what you wanted. If you knew that you had a particular taste for a certain kind of music, you could read Maximum Rocknroll and find something that’s in your ball park, even if you don’t like it or whatever. Stuff like Factsheet Five. Even the stores, good independent stores, of which there used to be a lot more. Eric: I think that’s the part that I miss the most, and I see it at Fantagraphics because we’re publishing just as many books as we ever have, but there’s fewer and fewer places for them to get reviewed and to get written about in a substantial way. I mean, you can get a blog review or something like, “This is the greatest thing I’ve ever read.” That’s cool, but actual good writing, good criticism, whether it be positive or negative, that’s the part that concerns me moving forward. I can really only speak for myself, but most of our engagement these days is with the consumer directly, like social media. Whereas, again, in the ’90s, we were working with these middlemen. You could say that eliminating the middlemen is great, and it’s great that we have direct rapport with our consumers, but I don’t know. Ultimately, I don’t think it’s a healthy thing. It just seems unsustainable. You have all these different companies that are just targeting their own direct consumers. It strikes me as less of a healthy environment. Eric: It really doesn't matter whether you're talking about comics or rock music. All of our culture is struggling with the same thing, but it's a hard thing to reconcile. It's like if you're in a band, on the one hand you can potentially find a huge audience overnight if the right circumstances happen, but on the other hand, where have all the rock critics gone that used to steer you towards the good shit? It's strange. I hate to sound like I'm getting into old man rants... This is an old lady’s project, so it's fine. [I mean, really. It’s called “20 years LATER”] Eric: Fair enough. I've said variations of this a lot over the years. Back in the '90s, you existed as much in opposition to something as you did in solidarity with something. People like the Hernandez brothers, they were operating in place of “We don't want to be this” much more than “We do want to be this." They were like, "Fuck Marvel and DC, and fuck mainstream pop culture. We're punk rock, and we're going to wear it on our sleeves, and that's that." But now you don't really have that. It's all one homogenized pop culture. I feel like now we live in a world where you don't draw those lines in the sand, where a punk band is seen in the same space as Lady Gaga. Eric: I think there's a phrase, “the good is always in opposition with the better”. I think that's true. Again, I lament the death of criticism and the lack of critical apparatus to write about culture, because I think that it does hinder some of that dynamic. “This is good, but it can be better, and it should be better. For this reason, this reason and this reason”. Now it’s like Friday Night Lights is the same as The Wire. They're both just “great TV shows”. They might be both very entertaining. But one is an entertaining melodrama and the other is a really sophisticated social commentary. They both have their virtues, but they're not the same thing. I remember when Strangers in Paradise came out and everybody compared it to Love & Rockets. It's entertaining, but it's not the same. Eric: Exactly. Strangers in Paradise is the Friday Night Lights. Again, I've never felt so many strange, conflictions in our culture as I do now, where, yes, you can make a strong argument that the art form of comics is healthier than ever. As an art form, it's more well respected than ever. It's read by a wider demographic of Americans than it has at literally at any point in American history. Yet, it's probably harder to be an artist these days than it's ever been. I think it's harder to make a living as an artist than it has ever been in my professional lifetime, which is going on over 25 years now. Do you think that is because of the cost of living in larger cities? Like Seattle is so expensive now. Eric: Seattle is its own problem, its own beast, and, yes, that's a huge issue here. In 1997 many cartoonists I interviewed lived in Manhattan, in Berkeley, in places they probably could not afford now. Eric: That's exactly right. You think about where Clowes, Adrian Tomine and Richard Sala all lived, on College Street in Berkeley. None of them could move there now. That’s why I chose Milwaukee. [laughs] Eric: It's great as an artist that you can have the freedom to move to somewhere a little cheaper, but even that doesn't solve the problem. I think it's still harder for a cartoonist to make a living now than I've ever seen. Part of it is that there's no illustration work. Illustration work was always a really healthy way for a cartoonist to make side money. That career is almost nonexistent anymore. There's a myriad of factors at work, but your options to make money and utilize your craft as a cartoonist have never been so few. Nowadays, I'd say the most common career path is probably storyboarding and animation, but you need to live in a hub where that's an option, like Los Angeles. Kaz is interesting to me, because he's writing for SpongeBob SquarePants, and then he does his stuff on the side. Eric: Kaz is an example of someone who did navigate it pretty well, because he was of that generation where he probably expected to have an illustration career, a magazine career in terms of getting his strips published in places, in The Lampoon or The Village Voice, whatever. Instead, he had to completely reinvent himself. He moved to LA and got into animation. He was able to transcend doing storyboards, and actually become a writer, and have a little more creative control. But for every one of him, there's a Debbie Drechsler that's just dropped out of the face of comics altogether, because she probably never wanted to move to LA. Before you could have an illustration career anywhere. Debbie Drechsler’s comics always looked like a full-time job to me, because they’re so detailed, although I knew she had a career as an illustrator. I am surprised she and others like her were not “stolen” from comics by the fine arts. There’s Joe Coleman, but I guess he never really did comics, except for those short stories. Eric: He did, he did a few, but not many. It's funny for someone who did so little comics, he's still associated with that world because his paintings do have this relationship to storytelling and representational cartooning. I'm really interested in what cartoonists do to survive, to be able to stay with comics. Eric: There are plenty of examples of people who've done it, good cartoonists and bad cartoonists. It can be done. I think in some ways, maybe the ways that they do it aren't necessarily for everybody, whether it comes to making merchandise or generating clickbait and advertising revenue that way. That's not for everybody. I think nowadays your best bet as a cartoonist is sort of similar to what I was saying about the publisher, which was that you're more and more having to kind of rely directly on your patrons, on your customers. I think in the here and now, that can be a great thing. But over time, it worries me because it seems almost like you're going backwards to the point where it's like the Renaissance and a painter has to rely upon his patrons. I think for a number of cartoonists it's become kind of a lucrative means of making a living as an artist, but there's a lot of cartoonists out there, and I don't think they can all survive that way. I just think it's getting harder and harder. I don't know where it ends at this point. That’s like a real weird dirty secret in comics. Everybody talks like, "Oh, comics are so healthy. Fantagraphics is doing pretty well”. We're having a pretty healthy run, yes, which for us just means not being on the verge of financial ruin. Like releasing the Peanuts books. Eric: Peanuts certainly helped. But we're done with Peanuts now. We've published all of it, and we're still doing more Peanuts stuff, but the financial stability that Peanuts afforded us when we really needed it, that period has kind of passed. We always had those things, whether it was Peanuts or pornography or Disney comics or even some of our bestselling contemporary authors. There's always been those things that have helped us. We've had enough of that lately that we're having a pretty good run, but again, I worry about cartoonists, and I worry about the infrastructure for supporting this stuff in the long term, because it's really precarious. You also have the store and gallery here in Seattle. Eric: It's a super tiny part of the business. For us, it's just a local place to have events. It's nice within the Seattle community for us to have that because this is our home and this is our community. It's great to have a presence in your own community. It's a minor part of the overall company, really small. It's a really small bookstore. It's great. I love it, but it's tiny. Drawn & Quarterly opened their store [Librairie Drawn & Quarterly] after ours. I think ours was a direct inspiration to them. They went bigger because there were few English language bookstores in Montreal. They went for a full-on neighborhood bookstore. Ours is a real niche alternative comics store. Are the audiences bigger? Like, is the audience for Love And Rockets, for example, bigger now than it was in the past? Eric: No, I would say that Love And Rockets in its heyday when the market was completely different, and comics across the board were selling a lot more, Love And Rockets probably sold three times what it sells now. I think back in the ’80s, when it was at its peak, it was probably selling between 20,000 and 25,000 copies per issue. Now the books can still sell well over time. The difference then was that the comic book market was much healthier. These days Marvel and DC have comics that sell under 10,000 copies. Thirty years ago in the ’80s, Marvel would cancel a comic that sold under 50,000. Now, 50,000 is a bestseller for them. That whole market has just completely changed. Like the Black Panther comic book. They got all these renowned writers to write for the series [Ta-Nehisi Coates, Roxanne Gay, Yona Harvey], but they cancelled the comic just as the movie came out. Eric: That makes perfect sense to me. Now you have a movie, you don’t need the comic. The movies do all the stupid things that the comics did, only better. Seven Spider-Man movies came out in the last 20 years. You don’t need any Spider-Man comics. It’s like evil has won. [laughs] Eric: Yes, I agree with that. Evil has won in so many ways. Like I said, Marvel is selling fewer comics than they ever have, but who are they selling to? The only fans that haven’t abandoned them yet. All the casual fans, they’ve all abandoned them. They’re down to their base. They’re like Donald Trump spouting racist epithets. They are catering to their base. That base doesn’t give a shit about Ta-Nehisi Coates. What’s my point? They’re set up to fail. Marvel’s on the one hand employing these good writers and talented people of color, but throwing them into an environment that’s openly hostile towards that stuff. They don’t give a shit about diversity. They want their fucking Thor comic, and they want Thor to be a blond-haired Adonis, and they want Black Panther to be what they know Black Panther to be. One step forward and two steps back again. Eric: Yeah. Up until the election [of Donald Trump] I really felt like, “We’re all on the right side of history. We’re moving in the right direction.” That every generation was more tolerant than the previous generation. You look at where we’ve come as a society in 100 years, and it’s pretty fucking awesome. Then this happens, and you just wonder, “What the fuck? Is everything I thought to be true not true? Are we just going to keep going backwards? Is this just an anomaly? Is this temporary?" We’ve had it pretty good there for a few years. Eric: I've always felt it's really easy to be cynical about the culture. I was definitely brought up that way, to have a healthy dose of cynicism, but I've also always felt pretty optimistic at the same time, with that hope, that clichéd hope that Obama talked about. I've definitely been a believer in that. Now I don't know what the fuck to think anymore. And there's an assault on truth too. Eric: I agree completely. Assault on truth is a good way to put it. Having a journalistic background, you can appreciate that probably more than a lot of people can. Going back to comics, it seems that a lot more kids are reading graphic novels now, outside of Marvel and DC. Eric: Part of my point before is that more people are reading comics than ever before, but they’re not buying them in comic book stores. They’re not reading the traditional types of stories that American comics have catered to in the mainstream. They’re reading stuff from Scholastic, like the Raina Telgemeier books, like Jeff Smith’s Bone, manga. Marvel and DC is like fringe culture at this point. The mainstream is books like Sisters and Smile. Younger people are reading comics that they’re not buying in comic book stores. They’re getting them from the libraries, they’re getting them at their schools. Eric: I feel like when I was a kid, you either read comics or you didn’t. If you read comics, you read superhero comics, maybe an Archie comic or something. It was really like a niche thing. If you read them, you were a nerd. That’s not a cliché to the point where when I got into high school, you kept it a secret if you read comics. That’s definitely changed. In my daughter’s elementary school, every kid is reading comics. There was no comics section in my school library growing up. There’s a graphic novel section, and it’s the most popular section in the library. It’s really stuff for everybody. There’s stuff for boys, there’s stuff for girls, there’s stuff for kids who like action, stuff for kids who just like to learn about science, there’s graphic novels about everything. That’s really great. And people who grow up reading comics are more likely to become artists. Eric: I think that’s true, and I think we’ll have to see over time how it all plays out. I also think the environment is healthier now. My daughter, she could actually enjoy Love And Rockets in a few years. When I was a kid, it was pretty unusual for a girl to go to a comic book store to buy Love And Rockets. Even though most of the girls who read Love And Rockets loved it, but most of them didn’t even know it existed because they wouldn’t go in the stores. I worked in a comic shop for five years in the ’80s. My girlfriend at that time hated coming into the store. I’d like to think that a lot of these younger people who are reading comics that traditionally wouldn’t have in the past could grow up to enjoy Chris Ware, Roz Chast, Alison Bechdel, or Jaime Hernandez. That’s one healthy aspect of things, I think. Comments are closed.

|

CategoriesArchives |

|

2421 S Kinnickinnic Ave, Milwaukee WI 53207

Open Mon-Wed 11-5, Thu-Fri 11-6, Sat 10-6 and Sun 10-5 | closing times may vary in event nights (414) 455.3498 | Contact Us [email protected] |

©

Lion's Tooth LLC, all rights reserved

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed